Part 5: How Can I Prevent Complications From Immobility? Musculoskeletal & Bones

Part 5: Musculoskeletal & Bones

Muscles and joints allow the body to move and carry out activities of daily living. Muscle weakness or joint stiffness resulting from immobility may impact on the patient’s quality of life1. Muscle atrophy is the most obvious side effect of long term bedrest2. The more trained and larger muscles, the faster the loss of strength and quicker the deconditioning process occurs. This can be as severe as up to 12% per week2. Usually, the first muscles to atrophy are those in the lower limbs that normally resist gravitational forces in the upright position.

Skeletal muscles lose tone when the feet are no longer weight bearing. A frequent complication of bedrest is contractures. These can begin to form in as little as eight hours of immobility3. Any decrease from the normal range of movement in the parts of the body responsible for motion (for example joints, ligaments, tendons, and related muscles) is known as a contracture4. It can be transient, such as after a heavy sleep, reversed by stretching in the opposite direction. However, 2-3 weeks of immobilisation will produce a much firmer contracture. Prevention of contractures maybe achieved through proper body positioning and body alignment, and the use of straps and supports along with regular Physiotherapy sessions with the patient.

The primary function of bone is mechanical support for body tissue and muscles, and also to maintain mineral homeostasis by providing a reservoir or calcium, phosphorous and magnesium salts5. When the body is engaging in regular exercise, osteoblasts and osteoclasts work at roughly the same rate. General bone density is maintained, and the skeleton is in symmetry. However, when the body is immobile, the mechanical loading of the skeleton is reduced, resulting in a decline of osteoblast that stops building the bone matrix, thus reducing bone synthesis, whilst the osteoclasts continue to break down resulting in the loss of bone density leaving the patients bones at risk of fractures.6

Approximately 110,000 people spend time in critical care units in England and Wales each year. The majority surviving to be discharged home. The general perception among patients, families and most healthcare professionals is that these people undergo a rapid convalescence and recover to their previous life, in terms of both quantity and quality. However, for many, discharge from critical care is the start of an uncertain journey to recovery. Family relationships can become altered, recovery from illness is highly individual, and few studies have been able to demonstrate a close relationship between features of the acute illness and longer-term impact7. As healthcare professionals, we should not underestimate the importance of early mobilisation, supporting the patients who can, to regain their independence.

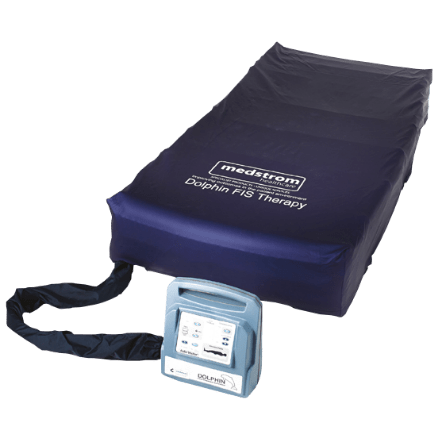

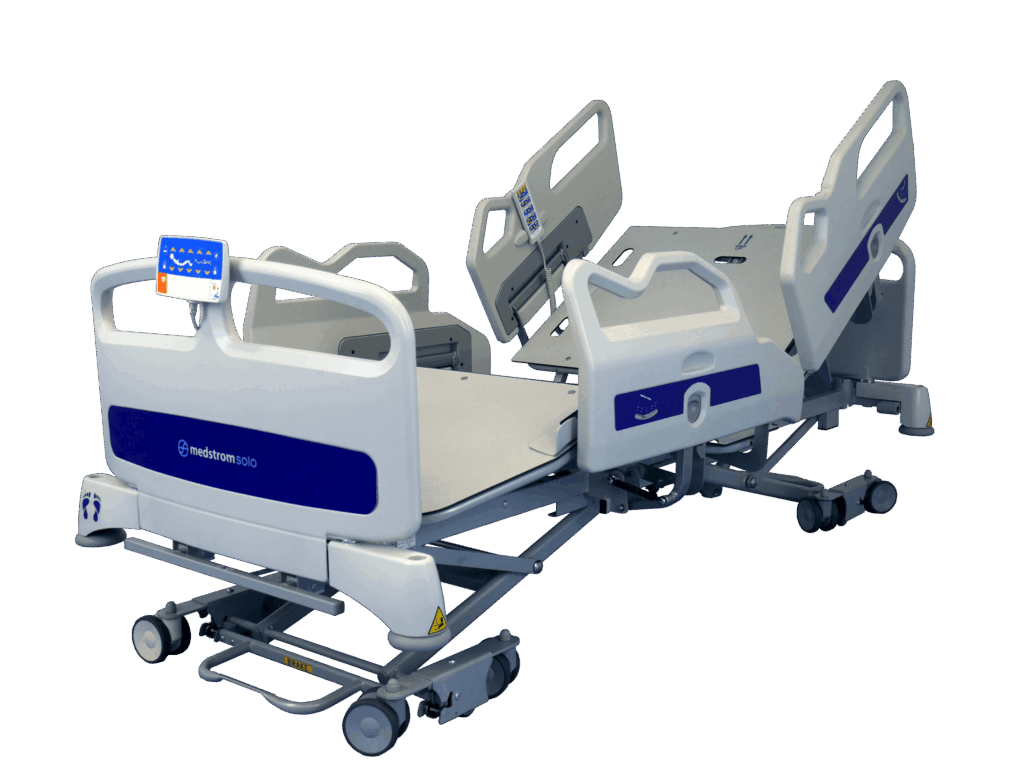

In addition to educating on the effects of immobility, Medstrom have a range of solutions that help to address getting the patient mobilised as soon as it’s safe to do so. For more information, see Eleganza 5 and Multicare.

Click the links below to read the rest of this series:

How do I Prevent the Complications of Immobility?

Part 4: Gastrointestinal and Renal

References

- Knight J, Nigam Y, Jones A (2019) Effects of bedrest 5: the muscles, joints and mobility. Nursing Times [online]; 115: 4, 54-57.

- Jiricka MK (2009) Activity tolerance and fatigue. In: Porth CM, Matfin G (eds) Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Corcoran PJ, (1991) Use it or lose it- the hazards of bedrest and inactivity. Western Journal of Medicine 154:5, 536-538.

- Montague SE, Watson R, Herbert R. (2005) Physiology for Nursing Practice. Physiology for Nursing Practice. London: Bailliere Tindall.

- VanPutte CL., Regan J., Russo AF.,Tate P., Stephens TD., Seeley RR (2017) Seeley’s Anatomy and Physiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. Dillingham TR(eds)Rehabilitation of Injured Combatant, Vol2. Washington, DC: Borden Institute.

- Lau RY, Guo X (2011) A review on current osteoporosis research: with special focus on disuse bone loss. Journal of Osteoporosis; 2011: 293808.

- NICE Guideline CG83