Skin Changes At Life’s End (SCALE)

In 2008, an expert panel was established to put together a consensus statement on Skin Changes at Life’s End (SCALE),1 which is still widely referred to today. In this post, I look at some of its key research, findings and recommendations.

Introduction

Pressure damage in the dying patient has been recognised for many years. Almost 150 years ago, Charcot described a specific type of pressure ulcer at the sacrum, shaped like a butterfly, which appeared shortly before death.2

More recently, in 1989, Kennedy defined the Kennedy Terminal Ulcer (KTU) as a specific subgroup of pressure ulcers developed by some individuals as they are dying. He described them as usually butterfly, pear or horseshoe shaped and situated predominantly on the sacrum and coccyx.3

What are the Risk Factors, Signs and Symptoms of SCALE?

SCALE occurs due to multiple factors, which are all inter-related. They include:

- Reduced tissue perfusion, which can cause:

- Inadequate skin oxygenation

- Decreased local skin temperature

- Mottling

- Necrosis

- Weakness and general reduction/limitation of mobility

- Poor nutrition and food/fluid intake:

- Loss of appetite can cause weight loss, cachexia and muscle wasting

- Dehydration

- Low serum albumin and haemoglobin

- Loss of skin integrity, for reasons such as:

- Incontinence

- Pressure, shear and friction

- Infection

- Medical device/equipment related damage

- Impaired immune system function

- A build up of metabolic wastes caused by multiple organ failure

Of all the above, reduced tissue perfusion is the most significant risk factor for SCALE, and it tends to occur first in extremities such as the fingers, toes, nose and ears. This chronic lack of oxygen to the skin, caused by many factors including dehydration, low haemoglobin and vasoconstriction can increase its susceptibility to damage.

What are the Possible Consequences of SCALE?

As organs start to fail, blood is diverted away from the skin and soft tissues to the brain, heart, lungs, liver and kidneys. Unfortunately, this means that even minimal pressure, shear, friction or trauma to the skin can result in major complications. These include skin tears, pressure ulcers, haemorrhage, infection, necrosis, and gangrene.

Is Skin Damage at End of Life Avoidable?

Whilst most pressure ulcers are considered avoidable, there is a consensus among experts that some are unavoidable.4 One of the causes of unavoidable pressure ulcers is the effects of SCALE. They can occur despite the application of appropriate interventions at all stages, which meet or exceed the standard of care.

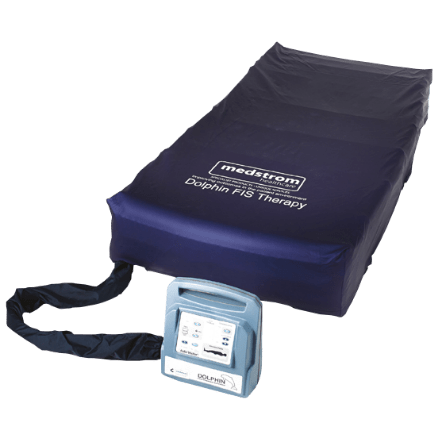

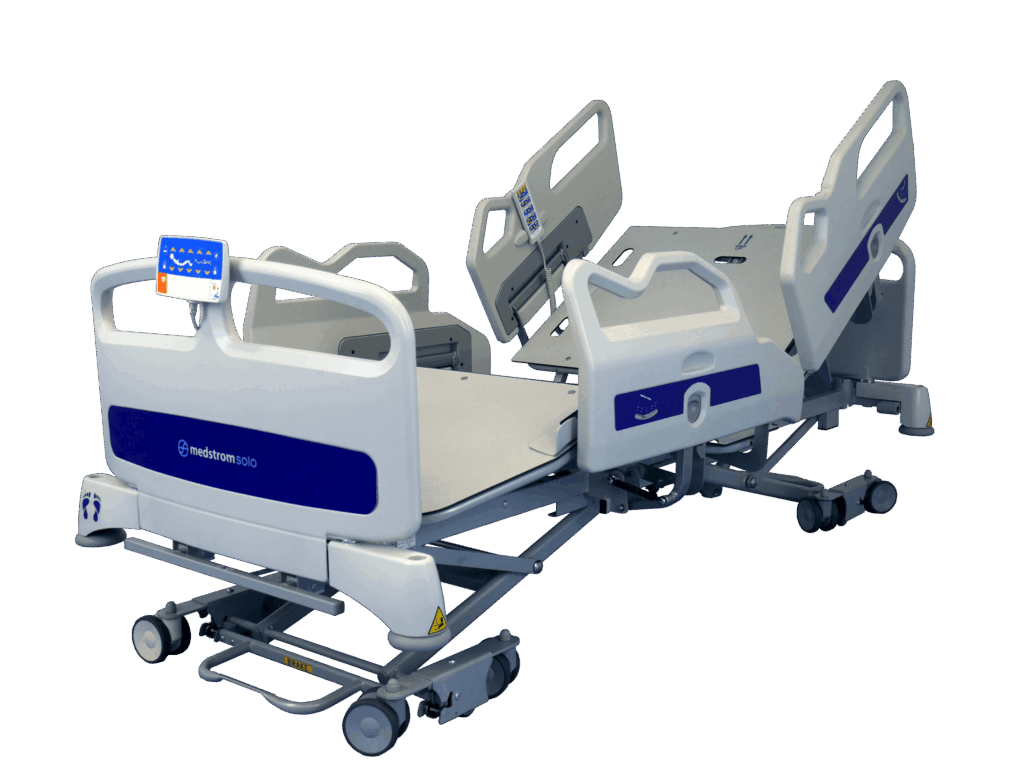

It may be possible to avoid skin damage at end of life by using a combination of measures. Regular repositioning may seem an obvious intervention, but this can be problematic if the patient is in pain, or has a preferred position that they keep reverting to. A support surface such as Dolphin Therapy, which helps to minimise pressure by immersion and envelopment, can also help.

Education

The SCALE consensus statement talks about the importance of educating patients and their loved ones about what they might see and experience as the patient nears the end of their life. It recommends explaining that:

- Skin function may deteriorate to a point where it is unable to tolerate minimal pressure or another insult without incurring damage.

- The patient’s skin may break down, even if all appropriate care is given.

- Mobility will deteriorate, which further increases the risk of skin damage.

- Patients frequently have a preferred position for comfort, that they may choose to maintain, even if they are lying directly on a pressure ulcer.

- Respecting the patient’s wishes is important.

With the knowledge that skin breakdown may be part of the dying process, people are better prepared, and will be less likely to be shocked or believe someone is to blame if it does occur.

Summary

There are still many unknowns about exactly what happens during SCALE. However, by knowing that it exists, and understanding the reasons why, clinicians will be in a better position to diagnose and manage it.

References

-

Sibbald R et al. SCALE: Skin Changes at Life’s End. Advances in Skin & Wound Care 23(5):p 225-236, May 2010. | DOI: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000363537.75328.36

-

Charcot JM. Lectures on the Diseases of the Nervous System. Translated by G. Sigerson. London, UK: The New Sydenham Society; 1877.

-

Kennedy KL. The prevalence of pressure ulcers in an intermediate care facility. Decubitus 1989;2(2):44-5.

-

Black JM et al. Pressure ulcers: avoidable or unavoidable? Results of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Consensus Conference. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2011;57(2):24-37.